We are designing digitally, but still constructing manually, says Stuart Maggs, CEO of Scaled Robotics.

Most people in the construction industry have a story to tell, often humorous: a column in the wrong place, a door that opens into a wall or a stairway to nowhere. But what this all alludes to is that the construction industry today is not working well.

Compared to other manufacturing industries it is wasteful and inefficient, still using the same technology as 100 years ago. So it’s no surprise that with such little technological advancement, 63% of the UK’s construction industry is operating on a 5% profit margin, 17% is losing money and only 20% operates above the 5% threshold.

However, it is unfair to say there has been no technological advancement. In the design and planning stages, software has taken great strides, going from 2D to 3D and now 3D to 4D. There is no denying construction is a digital industry – every architectural studio from the smallest to the largest relies on digital tools. A new generation of powerful software is capable of generating more efficient structural designs, just not possible in traditional ways.

A great example of this is the design of a 3D printed structural node point by Arup. The geometry of the node is optimised to reduce the amount of material required by 75%, whilst still performing the same structural function as the traditionally designed element. The complex shape of the node means that it can only be produced by a 3D printer.

So, it is not that we cannot design better structures or buildings, we just do not have the right construction tools to produce them. While buildings are becoming more complex, resources more expensive and margins get tighter, the tools to produce them have not improved.

This brings us to the root of the problem, we are designing digitally but still constructing manually. It is this disconnect between the digital model and the physical world that leads to many of the inefficiencies that plague the industry.

Nevertheless, these are not new problems. Other industries, such as automotive, have introduced robots to the production line 50 years ago automating the manufacturing process. This means they manufacture products of a higher quality more efficiently. Yet cars are standardised while buildings are unique, which poses another set of challenges.

Other manufacturing industries are using 3D printing as a way of creating complex and unique shapes not possible by other methods. Again the structural node point by Arup illustrates this, its manufacture only possible using a 3D printer.

However, the solution for construction is not just as simple as introducing robots or 3D printing. Applying existing technologies designed for other industries to construction does not work. For example, a 3D printer must be larger than the object it produces. Therefore, to 3D print a building, the machine must be larger than the building itself, which is simply not scalable.

At Scaled Robotics our goal is to digitise construction. We replace these large machines with “teams” of small mobile robots, thereby bridging the gap between digital and physical and working directly from the BIM model.

We are moving towards a future where construction is fully automated and we believe that 3D printing is one technology that will play an important role in the future of construction. This presents the possibility of building structures that consume up to 70% less material, without using costly moulds and scaffolding, creating shapes that were either not possible or not financially viable due to the limitations of traditional methods.

Ultimately, though, such advances are only possible step by step. The logical progression is to start by using robots to perform tasks that drastically improve current workflows, then move on to more complex tasks such as 3D printing. It’s a case of learning to walk before you can run.

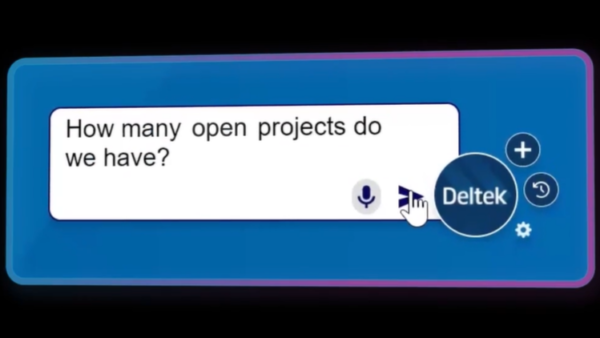

So how does Scaled Robotics fit into this process? We are currently developing robots that directly link the physical world to the BIM model, with the capability to find construction errors in real time by comparing the BIM model to the environment and locating errors in construction before they become costly. This puts valuable information into the hands of the people that need it the most.

Comparing the digital model to the site is not new, but right now it is painfully slow. It takes hours or days, even with the availability of a total station or 3D scanner. A complicated process that leaves room for interpretation and error.

So if BIM has played a vital role in the digitisation of construction, now it is time to match the capabilities of digital design to real-world digital construction tools, and at Scaled Robotics we believe the introduction of robots to the job site is the crucial next step towards the digitisation of construction.

We are designing digitally but still constructing manually. It is this disconnect between the digital model and the physical world that leads to many of the inefficiencies that plague the industry.– Stuart Maggs, Scaled Robotics