A unique collaboration between a New York architect, a London museum, two IT corporations and some 430 volunteers around the world has just completed the first stage of a scheme to resurrect one of the world’s lost masterpieces of building design – Sir John Soane’s Bank of England.

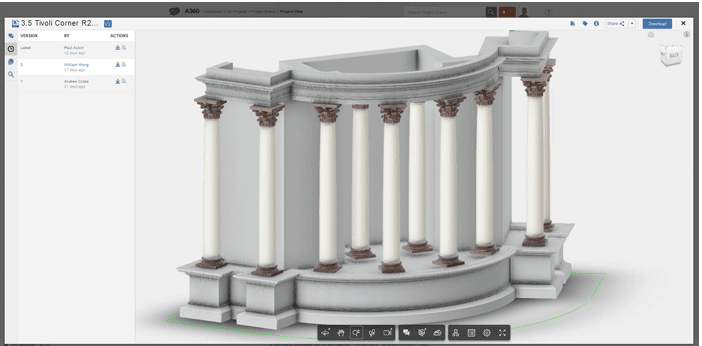

The project involves taking the existing drawings and other documentation of Soane’s designs, as well as the photographs that were taken before they were demolished between 1925 and 1939, and use them to create a crowdsourced BIM model of some of the best known elements.

But how can a single model be created by more than 400 uncoordinated volunteer workers? BIM+ talked to Graham S Wyatt, a partner at New York-based practice Robert AM Stern Architects (RAMSA), who chose Soane’s lost masterpiece as the subject of the initiative.

Project Soane arose out of a competition run by Hewlett-Packard for the past three years to find the best computer-generated images in a variety of fields. Last September, HP approached Wyatt to ask if he would be interested in helping to organise a category for the best rendering of a building.

The idea was that RAMSA would offer a building model to be used as source material for the competition, but Wyatt perceived problems. “There are often issues of client confidentiality and unless a project is totally finished, often a model is not fully developed so you have to be careful about releasing it,” he says.

“Then I said, what if we selected a building that is familiar in the world of architecture but for which no model exists? They said well, what would you suggest? And I thought about different buildings but I will admit that I have a personal obsession with Soane’s Bank of England, so I chose that.”

The project has tapped into the interests of several groups

This then led to the establishment of a crowdsourced project to recreate some of the neo-classical bank. At first Wyatt had the “nutty idea” of tackling the entire three-acre site as it was in 1920, but after a closer look at the documentation available at the Sir John Soane museum in London it became apparent that the record was incomplete, and that much of the work was done by other people.

This resulted in a pragmatic decision to tackle areas where sufficient documentation did exist. “It was a bit disappointing to me, but I think it was absolutely the right thing to do,” Wyatt says.

The project has tapped into the enthusiasms of a number of disparate groups: those who are interested in the work of Soane; those interested in crowdsourcing; and those who are interested in architectural rendering – all three groups have now been exposed to each other’s worlds.

After signing up to work on the model, volunteers were given access to Autodesk Revit and the necessary papers in the Soane Museum’s archive, and were encouraged to construct a digital copy of a particular area.

Wyatt says: “We are doing a couple of the principal facades, which are quite long, and then we are doing two of the best-known interiors which are really complicated spaces.

“It’s not deeply difficult to do, but the geometries are complicated and getting the details right is not always easy and although the documentation is pretty good, it’s not complete.

Some photographs of Soane’s original buildings remain, including this of the Consul Office

“There are a variety of drawings, some of which show large areas but not in a high level of detail and some of which show small areas in a very high level of detail but it’s not as though they come together into one comprehensive set of drawings. Some things need to be extrapolated.”

One obvious problem with the crowdsourcing method is in determining how accurate the model will be once it’s finished. Fortunately there are some photographs of interiors such as the Consul Office, where gilt-edged bonds were handled, but also some guesswork – Wyatt says the skills involved are archaeological as well as architectural.

“There will be purists who look at this and try to say how correct it is, and there are some things that if I were in the model I would correct, but this is the nature of crowdsourcing – we sent out an email encouraging all the participants to go back and look at the model again and the original drawings, so it’s an interesting test.”

A computer consultancy called CASE has offered to help fit the hundreds of models together, and Wyatt says if somebody wanted to edit the results, that could be done. “I’m sure that if the Sir John Soane Museum wanted to release an official model they would probably go through a process of design quality control and editing, which has not yet taken place in the crowdsourcing environment.”

It should be added that the project that began as a competition continued as a competition, and there will be prizes of HP hardware for the participants who make the best contribution to the final model, including achieving the best historical accuracy.

The modelling part of the competition closed on 15 November, but a second phase, to add rendering and visualisation to the model will begin in December, and is open to new entrants.

The lost treasure

When the models are completed and rendered, what will they tell us? To answer that question, a short excursion into architectural history is required.

Sir John Soane’s day job was as architect and surveyor to the Bank of England, and he held the position for 45 years. When he resigned in 1833, most of the Bank’s three-acre footprint had been remodelled in some way, and a number of spectacular set-piece facades inserted.

Sir Nikolaus Pevsner described Soane’s interiors as filled “with an infinite variety of domes”

In the wake of the Great War, Britain’s national debt grew to such an extent that Soane’s bank was too small for the business to be transacted; unfortunately, this renovation was done by the architect Herbert Baker in a way that virtually erased Soane’s work.

Sir Nikolaus Pevsner described Soane’s interiors as filled “with an infinite variety of domes, every one original and interesting, and several of a very high and exacting beauty”, and their destruction he called “the worst individual loss suffered by London’s architecture in the 20th century”.

So, the test for the final model is whether it is able to recreate Pevsner’s sense of unexpected delight, and also whether it conveys Soane’s success in bringing natural light into the bank despite the absence of windows on its exterior facade.

This is one of the key tests for Wyatt: “Soane’s design was careful to bring all this diffuse light in from the top and the architectural devices are very interesting and sophisticated,” he says.

Another interesting question that remains to be answered is what exactly happens to the model once it is complete. Wyatt points out that the scheme was only conceived last year, and so it’s relatively early days, but already some designers are beginning to nudge the work in new directions.

One has produced a wire-frame model of the whole bank that the finished renderings fit into, and in the future it may be seen at part of a CGI rendition in a film or computer game.

“A lot of people are talking about what they might do with it and that’s part of the whole thing for me,” says Wyatt. “One of the things I like about this is that it isn’t really our model – it’s everybody else’s model. We’ve just launched the process and watched this happen.”

There are a variety of drawings, some of which show large areas but not in a high level of detail and some of which show small areas in a very high level of detail but it’s not as though they come together into one comprehensive set of drawings. Some things need to be extrapolated.– Graham S Wyatt, Robert AM Stern Architects