‘Digital twins cannot be conceived as simple asset information models, because they work as real-time simulators of the built asset’s performance and users’ operational occupancy modes.’ Angelo Ciribini

Angelo Ciribini from the University of Brescia and The European Council on Computing in Construction (EC3) asks if the growth of data management will mean tech giants and the construction industry working closer together.

Participants in the AECO industry are more and more used to generating data on a computational basis and to exploiting its value.

But a large portion of the produced data sets remain poorly machine readable or, at least, unstructured.

The Common Data Environment itself appears as a Common Document Environment, too.

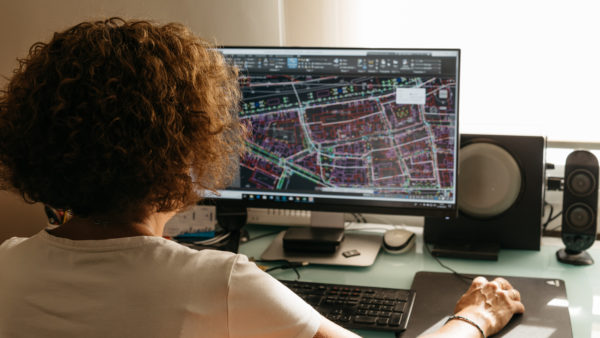

However, the AECO industry has entered the world of the computational data to manage the digitised built environment.

Such a world is currently controlled by the giant tech companies (for example Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Siemens to name a few) which are more and more concerned with the AECO markets by means of various strands, including: bi-oriented cloud-based digital platforms, web-based virtual RE markets, home speakers, building automation, AI-purposed cognitive algorithms, building & MEP components-oriented digital marketplaces.

These strands would impinge upon the so-called (according to Accenture) Living Services, entailing the provision of a large amount of hyper-personalised services.

Moreover, the Amazon-controlled Alexa Fund is investing in plant prefab and Airbnb is designing unprecedented offsite buildings through its internal design studio Samara.

On the other hand, WeWork (We Company) does provide sophisticated Spaces as a Services.

Consequently, tech companies are competing by means of large digital ecosystems, incrementally including the GIS- and BIM-based AECO industry players.

The former do act depending on the paradigm of the surveillance capitalism, often offering disintermediated services and focusing on users’ and customers’ lifestyles, users’ behaviours, and cycles of lives (for example when assisting and supporting ageing people).

The AECO industry’s traditional players would more and more be forced to compete within such digital scenarios and landscapes.

It does imply that their own information models would be more effectively structured as far as data models are concerned. And it means that any data sets could be semi-automatically processed in choosing the design options or in checking the design code compliance.

Likewise, the built assets become sensorised and interconnected, leading to the rise of digital twins.

Digital twins should allow to simulate the built asset’s performance and failure modes in real time as well as users’ and occupants’ behavioural patterns and occupancy flows.

Digital twins cannot be conceived as simple asset information models, because they work as real-time simulators of the built asset’s performance and users’ operational occupancy modes.

They engender large flows of structured and linked data sourced from the physical built assets to be addressed towards the digital platforms or ecosystems, managed by the tech giants.

The convergence that occurs between the AECO industry’s players and these tech giants could be represented by a sort of configuration system capable of matching and trading off space units, physical components and, above all, behavioural patterns.

Eventually, a key question does need to be answered: will the giant tech companies replace the traditional AECO industry players or will they cooperate together?