Peter Egan from the Corps of Royal Engineers explains how using digital technology is helping the UN and aid agencies do more with less by reducing construction waste, strategic costs and improving operational practises and maintenance.

The problem

Since the end of the Second World War and more recently the 9/11 attacks the world has become a more turbulent place. Organisations like the United Nations (UN), World Health Organisation (WHO) and aid agencies are now spread across the globe providing key life supporting aid and security – the UN alone is active in 14 peacekeeping missions worldwide and has conducted more than 70 missions in the last 70 years.

This support is criterial to sustaining basic quality of life for millions of people, but this is not just as simple as providing food and water. Each venture requires a large supply chain network, temporary and long-term accommodation, local training and medical facilities for both refugees and the aid providers, as well as road and runway projects to keep supply routes open.

In fact, a large part of any aid or peacekeeping mission is the provision and maintenance of infrastructure, but in today’s competitive skills market aid agencies and the UN have found it hard to find the breadth of skilled experience needed to support a wide range engineering and construction roles.

Even with the best intentions, providing quality engineering solutions in all their locations has become a struggle due to a lack of experienced professionals. Many projects are designed locally with little knowledge of basic engineering principles in areas such as drainage, water supply and power generation, relying heavily on international supply chains for materials. In my experience many organisations rely on military engineers and volunteers to provide short-term specialisms, with local engineers doing their best in between.

So this problem poses a question: if they cannot get an experienced engineers regularly to the problem how can the problem be simply brought back to the engineer?

UN field engineer-installed septic tank

The requirement

Modern technology can now place individuals in virtual environments with little equipment support other than a mobile phone, a VR headset and internet connection. Many, if not all, aid missions have a mobile internet connection to support their work.

So could technologies such as 360 cameras and photo scanning with basic geological data be enough to bring a rear based engineer into an austere project environment, providing design, resource and construction information at each stage of the project.

My team at 36 Engineer Regiment, which is a part of the UK’s Corps of Royal Engineers in partnership with TERRA Measurement, have been investigating this principle using 3D scanning, photogrammetry against traditional measuring techniques, to capture site information to be set back to a rear based design team.

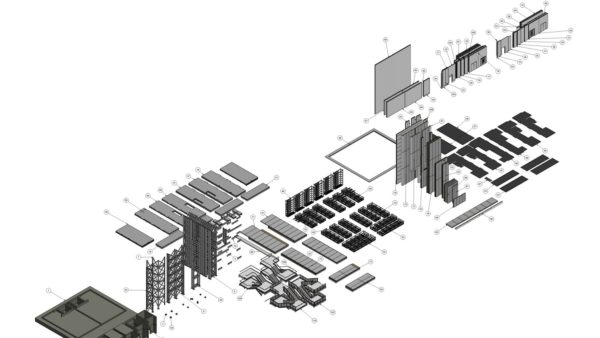

Digital working now allows onsite captured data to be shared and reworked. Apps such as Sketchfab, Kubity and Google Cardboard allow multiple partners to share 3D models, in some cases hold live in model discussions and even print project components.

This approach with modern design software such as AutoCAD Revit or Trimble Sketchup allow designers to create detailed interactive design models incorporating material information and supply data, which would allow in the field engineers to know how the designer intended them to be used.

But more information is not just the answer. More simplified designs using standardised pieces and where possible vernacular techniques and materials, would reduce the logistic burden while condensing the need for a wide range of technical skillsets on the ground.

Simple digital suites with app-based predesignated design sets would allow engineers to easily order pre-set barcoded stores lists, with the intent to fit out vernacular resourced structures, constructed from design models facilitating BIM-enabled aid missions. The key to this process is simplicity: simple designs, simple stores lists and localised training, reducing on-site complications and difficult supply chains.

TERRA Measurement and 36 Engineer Regiment Design Team at St Catherine’s Chapel, Dorset

The opportunity

In my career I have worked across the Middle East and more recently Africa. I have worked with a range of people with different skillsets and competences, some were extremely effective, all wanted to create an outcome for the better; many just didn’t know how to do so, or lacked the right skillset to do it correctly.

This skill shortage creates a great opportunity to help the UN and aid agencies do more with less by reducing construction waste, strategic costs and improving operational practices and maintenance. So, is digitalisation the answer to a growing professional skill gap? Could first world engineering be inserted directly into third world infrastructure projects? Could the use of apps reduce onsite technical conflicts and ease the strain on stretched resourcing supply chains?

Digitalisation may not solve every issue – the generation of a coordinated platform which can enable engineering infrastructure solutions to be simply designed and resourced by a low skilled workforce with limited engineering experience, is from my perspective necessary.

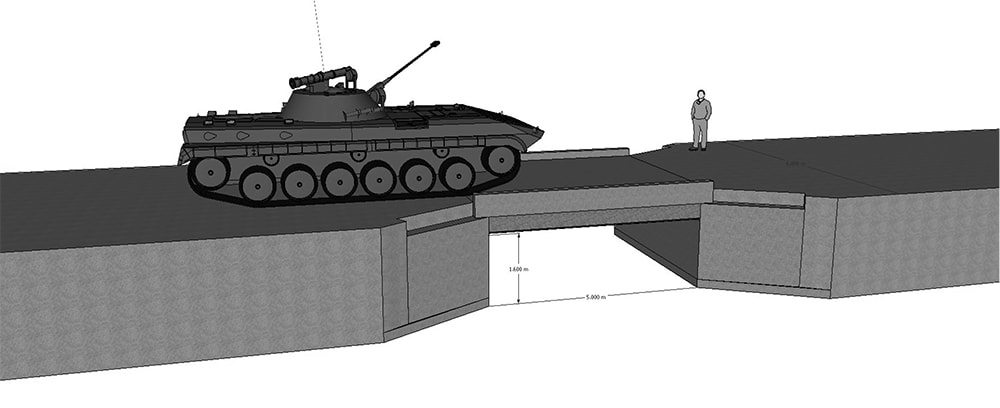

Concept model of Kodok bridge, Western Nile, South Sudan

An example of this approach was achieved with the UK’s interjection on Operation Trenton with the UN in South Sudan. On arrival it was clearly identified that road and runway repairs in the northern region were inadequate and required regular reworking. This issue was mainly caused by under-resourcing due to difficult and long supply chains alongside costly materials.

Following an existing system used by the UK military, Tensar International was asked to help improve local quality by creating a bespoke programme which combined local materials and Tensar products. The resulting programme only required the input of basic CBR readings and user requirements into the software to generate a full design and material specification, greatly reducing material quantities, overall costs and the mission’s emissions footprint, while increasing usage and bearing capacity.

This type of innovative approach fits well with the UN’s 17 sustainable goals and will, if continued, help the UN achieve its strategic aims at an operational level.

Organisations like the Corps of Royal Engineers will continue to strive to innovate new adaptive means of operating in austere environments alongside the many essential volunteer groups, but the question is now just how far can these means go and can the limits of digitalisation be pushed towards maximising this effort to meet all our sustainable goals?

Industry-led innovation in digitalisation is where the greatest effect can be made, changing the way we work, while opening up new products to assist third world problems, providing key long-term support and mentoring.

Peter Egan is principal engineer, Op Trenton 5 UNMISS, Corps of Royal Engineers