How do you approach nuclear decommissioning with robots? A new white paper from KUKA Robotics reveals what’s been happening at Sellafield.

As nuclear decommissioning is a relatively new technology, lessons are being learned – and applied – from year to year.

The joint venture of Bechtel and Cavendish Nuclear (a subsidiary of Babcock International) is approaching some of the more difficult decommissioning projects – where waste forms and legacy plant conditions cannot be ascertained with any confidence until retrievals begin – with a “Lead and Learn” strategy. The idea is to provide technology to start retrievals with flexibility to adapt it as further learning is gained – and that means robotics and automation.

The JV is using equipment from KUKA Robotics on its Nuclear Decommissioning Agency contract to handle radioactive waste at Sellafield’s pile fuel cladding silo (PFCS) recovery and storage cell.

The PFCS, which was built in the 1950s, was filled over several decades primarily with aluminium pile fuel cladding, which is stripped from fuel rods when they are removed from the reactor, for reprocessing. The silo also holds significant quantities of Magnox magnesium cladding and other items, which were not recorded in detail.

The atmosphere inside the silo is inerted with naturally fire-suppressant argon gas. The JV’s contract requires it to access the legacy waste, remove it, and load it into containers ready for transfer to safe, longer-term storage.

Glenn Moss, engineering manager at Cavendish Nuclear, says: “The waste has been in the silo for 50-plus years and it was not built with emptying in mind. Delivering the project is very, very difficult.”

A KUKA robotic arm seals the lid on the container of radioactive waste (Image courtesy of Bechtel)

Having initially looked at designing robotic systems from the ground up specifically for nuclear decommissioning applications, the JV determined that this approach constrained design and effectiveness. It decided to prioritise the processes and look for automation, robots and remotely-guided vehicles technology that could be either bought off the shelf or readily adapted for those processes, which is where KUKA comes in.

Dave Burns, nuclear technical sales and project manager at KUKA, acknowledges that challenges with radioactive waste are currently led by the fact that a lot of the waste is unknown. “The documentation of what went into the pile cladding silos at Sellafield, for example, was not as robust as could have been wished and was incomplete, in parts,” he says. “We have to cope with those unknowns and learn to design round them.”

“We engaged with KUKA quite early on,” Moss says. “There is a lot of confidence in KUKA robots in radiation environments, both medical and in higher radioactivity situations. They provided the concept and the preliminary design of the work cells and a lot of work on the PFCS recovery and storage cell at Sellafield.”

The process and methodology were rehearsed on a replica and training retrievals site at Babcock’s facility in Rosyth, Scotland.

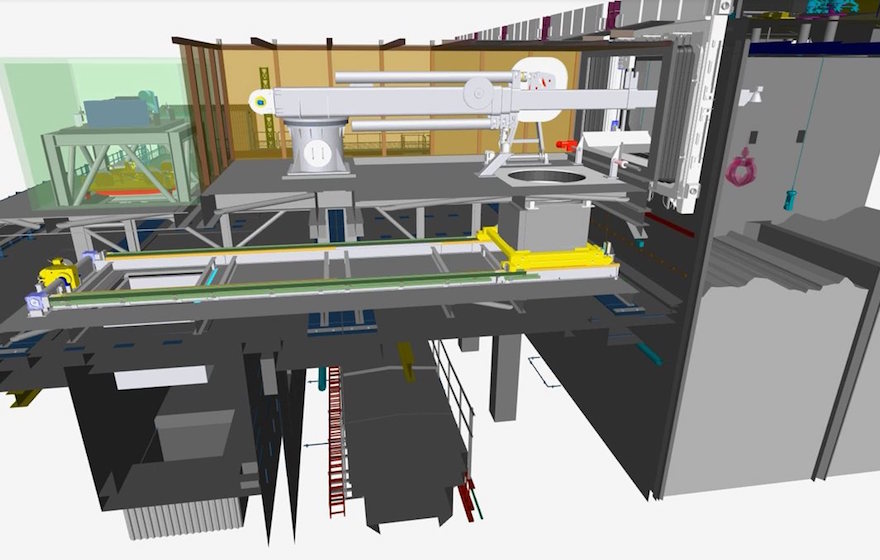

A digital rendering of the robotic waste retrieval arm installed on the superstructure built onto the pile fuel cladding silo (Image courtesy of Bechtel)

But it’s not simply a case of sending the robots in: while their motors and metal tools are not easily damaged or degraded in radioactive environments, their ‘brains’ – the circuit boards and control boards – are. “KUKA has designed robots that can have the sensitive circuit boards and control boards remotely mounted,” Moss says.

This means that they can be placed in a shielded environment, while bench or floor-mounted robots can be operated or automated to get on with their tasks within the hazardous area. “The plant has no operator or manual intervention in any of the retrieval process, including bolting the stainless-steel containers,” he continues.

The PCFS has a KUKA KR150 six-axis, floor-mounted robot within the cell. An automated guided vehicle brings the stainless-steel containers to have their lids unbolted, before being lifted 14m, lid removed, and the container filled, then lowered back to have its lid bolted down again. “The robot has to do its job reliably,” Moss emphasises. “The KR150 has six axes and if one axis fails, we can remotely use a configuration of the other five to reposition the robot allowing the container to be moved out of the way and allowing access.”

The staff operating the process have received special training and gained new skills in operating the automated equipment.

Looking to the future, Burns adds: “We have been doing work on how to sort, how to examine areas – with remote cameras or with sensors – and how to categorise the hot areas, the radioactive areas, and how to sort everything remotely, without putting operators at risk. Going forward, we are involved with developing AI as well as remote-controlled and operated machinery.”

Read the KUKA white paper

Watch Bechtel’s video

Related articles

- Digital twins set to revolutionise nuclear decommissioning

- First nuclear decommissioning robot contract awarded

- Digital twins to monitor nuclear plant structures

Main image: © Steve Allen | Dreamstime.com