Nearly a month ago, BIMplus highlighted how the Crossrail project team learned the hard way the trouble associated by not setting information management requirements at the start of a project. Malcolm Taylor was head of technical information on the mega-porject for a decade until 2019 and here he reveals the full scale of the challenge that Crossrail faced.

The article on 18 March 2024, titled ‘Crossrail and the information management lesson learned’, reflected on the report prepared for the Department for Transport (DfT) and the Infrastructure and Projects Authority, Sponsoring a Major Project – The Crossrail Experience. In particular BIMplus focused on the ninth lesson learned: “The sponsor’s requirements should stipulate integrated digital asset management data in design and construction.”

From an asset management and information management perspective, this is a really important and critical conclusion with which we would all agree, noting that with Crossrail, there weren’t given any such requirement from its sponsors (DfT and Transport for London). But there is much more to this than simply saying in hindsight that there should have been systems and processes in place. The report implies this wasn’t thought about which reflects on both the sponsors and Crossrail itself.

What actually happened?

Early in the design process, Crossrail recognised that the asset information requirements of the future maintenance organisations – Network Rail and London Underground – were, to say the least, not compatible or appropriate to the future type of infrastructure being proposed.

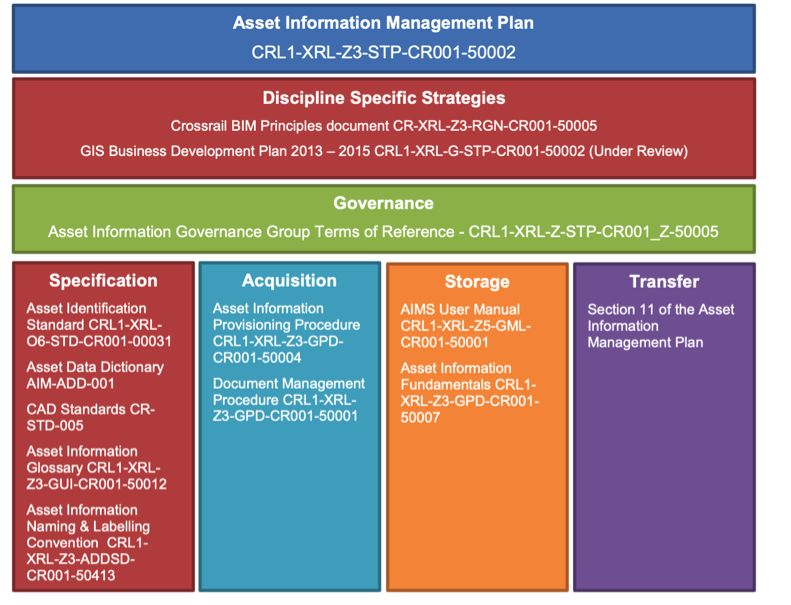

Also, with data for more than 500,000 assets provided by more than 50 construction contracts for one railway, it was important to get a standardised single system in place. So, in 2010 Crossrail published its Asset Information Management Plan. Over the next few years, detailed processes were put in place for creating a consistent set of asset information across multiple design and construction contracts (see below).

In the absence of anything from the future maintainers, this includes a standardised detailed definition for each asset. A number of these documents, including the entire Asset Data Dictionary are all still available in the Crossrail Learning Legacy website.

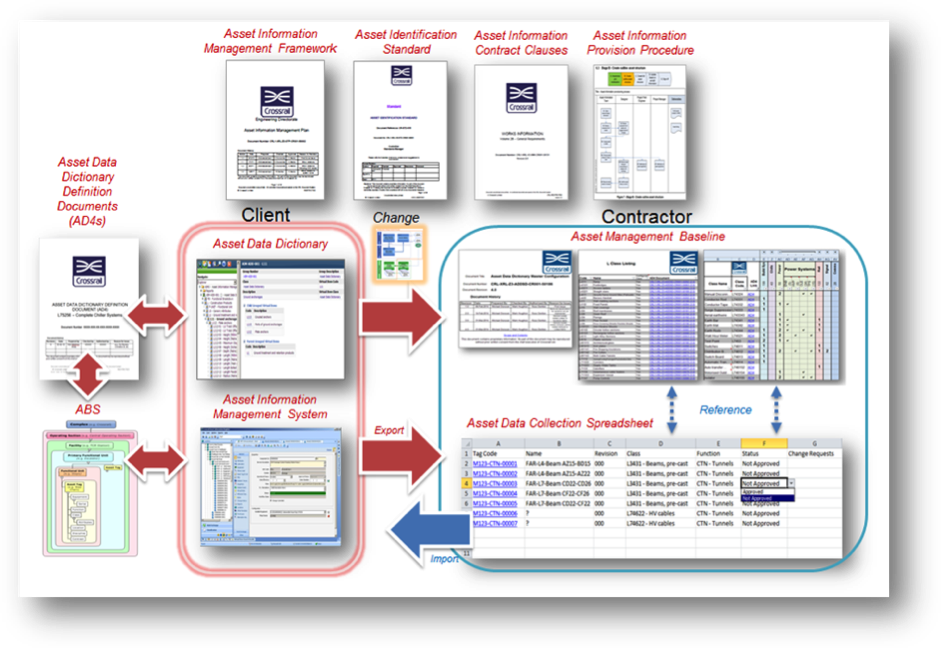

Contractually, every designer and contractor was required to follow this process as it was set out as a requirement in the Works Information General Requirements Volume 2B Clause 13.5 (shown diagrammatically in below).

All asset data was compiled by contractors and Crossrail staff into the project CDE. This CDE was a set of relational databases where the asset data was linked (related) directly to O&M manuals, certification, documentation, etc. This even included sustainability ratings (using BREEAM) as metadata to individual assets.

It’s also worth noting that for more than six years there were regular formal meetings every two months between Crossrail, Network Rail, London Underground and Rail for London specifically to coordinate and agree the final outcomes.

Why didn’t this work out?

When you’re digging tunnels, pouring concrete and battling against time, it’s always a struggle to keep people’s attention focused on the importance of asset information management – this included Crossrail staff as well as contractors. Contractors were used to compiling asset data in their own way at the end of construction and some were resistant to new ways of working: people behaviour problems far outweighed any technical BIM problems we ever had!

And when the project began to hit difficult scheduling issues in 2016, the interest gap became bigger and tougher. As contracts were renegotiated for closeout, it was always easier for contractors to do their own thing in their own systems, and the centralised control of the CDE by the remaining Crossrail staff slipped away – resulting in the inconsistencies and gaps and paper trails noted in the report.

The concept of the CDE passing into operation and maintenance never happened – London Underground and Rail for London took out the data they wanted from the CDE for their own systems, the former for their spreadsheet-based system, and the latter for their emerging newly developing asset management system. The CDE was eventually archived after handover as a data store and the BIM principle of a single source of truth disappeared.

The DfT/IPA report noted that the Crossrail project sponsors faced a challenge as BIM was a “relatively new way of collecting and integrating asset data when the sponsors’ requirements were written”. While the evidence would suggest Crossrail had a good understanding of BIM in design and construction (for example, winning British Construction Industry Awards for BIM in 2013 and 2015), taking BIM principles into operation and maintenance requires a similar commitment and understanding by organisations responsible for those activities – and that’s a big ask…

An alternative conclusion

The ninth lesson learned (“The sponsor’s requirements should stipulate integrated digital asset management data in design and construction.”) is absolutely right. However, I propose this should go much further and – using BIM principles – link directly to outcomes in the operation and maintenance environments. With a delivery model like Crossrail, you can create systems and processes for creating asset management data, but getting this data into existing organisations and systems that sit outside your contractual boundaries has significant assurance and risk issues. Asset information management can struggle to be heard, especially when contractors are demobilising and other teams are focusing on testing and commissioning.

For new infrastructure, sponsors should get the delivery organisation to create an integrated enterprise asset management system with the physical system itself, not just the data. This can then help ensure:

- The physical and digital worlds are integrated seamlessly and concepts such as digital twins can be optimised from the start and delivered at handover.

- The maintainers get the most up-to-date asset information management systems in place, not left having to push new data into old systems.

The advantages for an existing maintainer almost certainly outweigh the disadvantages. By being involved in setting the delivery requirements and prescribing outcomes, they can get the latest new technology and processes in place. They don’t have to worry about the constraints of their existing systems.

And finally, this approach gives them the future opportunity to upgrade their legacy asset information management systems over time into their new – and hopefully – state of the art digital systems based on the latest data-centric BIM and ISO 19650 principles.

Malcolm Taylor is an independent specialist in programme and project information management. He is a non-executive director of nima and is an expert adviser to Crossrail. He was head of technical information at Crossrail, initially under secondment from Aecom, from March 2009 until May 2019.

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Excellent summary